From 1764 to 1772, 30,623 colonists arrived in Russia to start new lives on the Russian steppe. Most of the families came from German speaking lands although a small number came from other parts of Europe such as England and the Scandinavian countries.

As soon as the would-be emigrants had signed their immigration contracts and arranged their affairs, they were assembled in a few centrally located cities, where the Russian agents found them temporary living quarters and gave them daily allowances for food. When sufficiently large numbers had been assembled, they were transported to one of the Baltic ports, usually Lübeck, from where Hanseatic or English ships took them east across the Baltic Sea into the Gulf of Finland to Kronstadt, near St. Petersburg. Lübeck was an especially busy point of immigration with over 72 percent of the colonists leaving for Russia sailing from this port in 1766 alone.

The 900 mile voyage by ship from Germany to Russia could normally be made in 9 days. Inclement weather and unfavorable winds could prolong the journey to several weeks. Sometimes dishonest ship captains would delay which allowed them to sell provisions at inflated prices as the colonists' supplies diminished. In one case, the journey from Lübeck to Russia lasted three months.

Many left their homes to escape a war-ravaged Central Europe that had suffered socio-economic devastation wrought by the Seven Year's War which ended in 1763.

Recruiters under the employ of Catherine II (Catherine the Great) were sent to many areas of Central Europe with her Manifesto which invited people to migrate to Russia. By 1798, there were more than 38,800 individuals living in 101 German speaking colonies along the Volga River near Saratov.

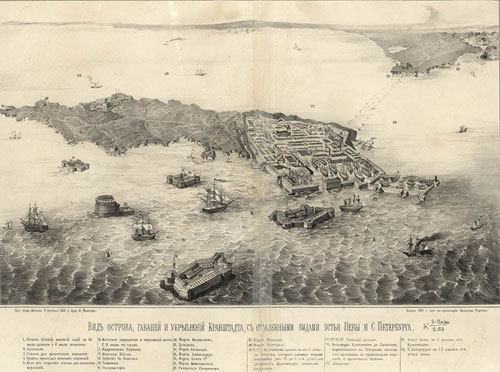

Immigrants traveling from the German lands would first arrive at Kronstadt, a Russian naval Port located on a island in the Gulf of Finland west of St. Petersburg.

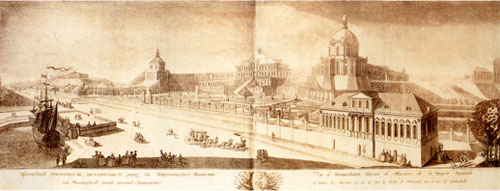

From Kronstadt, the colonists were taken to the city of Oranienbaum (Lomonosov) on the mainland. Oranienbaum is located near St. Petersburg and was the site of one of Catherine's royal residences known as the Great Palace of Oranienbaum. Catherine had elected to make her murdered husband's (Peter III) palace her summer residence after his death in 1762. The palace is built near the shore of the Gulf of Finland, just opposite of the island on which Peter the Great had situated the Kronstadt Fortress that protected St. Petersburg. A canal ran from the shore to the palace, making it possible to sail almost to the gates of the lower garden.

The colonists were often lead in the oath of allegiance to the Russian Crown by the German pastor of the Lutheran Church in Oranienbaum. It is reported that Catherine herself would sometimes welcome the colonists in their native German language from the balcony the Great Palace which faces the Gulf of Finland.

From 1766, the reception and housing of the colonist was the responsibility of the Titular Counselor, Ivan Kuhlberg. Kuhlberg also recorded and compiled lists of the colonists as they arrived in Oranienbaum. More than 20,000 persons, or 6,500 families are reflected in the Kuhlberg lists. The lists are compiled by ship, with an indication of the date of arrival in Russia, port of departure, the name of ship, and the name of the captain. The given name and surname of the colonists are listed along with the composition of the family (age of children was indicated), location from which they came, religious confession and place where they desire to settle. From these lists we know a few of the ship names such as The Elephant, Love & Unity, and Anna Catharina.

In Oranienbaum, the colonists they were given materials to build huts for their temporary accommodation while they waited for the next move. Arrangements for their accommodation were of the most primitive kind. Colonists remained in Oranienbaum from two weeks to several months making preparations for the long journey to their new homeland.

For the first time, the immigrants saw the general backwardness of Russia. Most disappointing to many of them was the fact that, in spite of the promises that had been made, they were not free to go where they liked in Russia. Many of the colonists intended to pursue their trades near St. Petersburg where there had been a sizeable German community since the time of Peter the Great. Most colonists were compelled by Russian officials to join the majority of the settlers in developing the agricultural lands on the lower Volga River near Saratov. However, some colonists were settled in areas of St. Petersburg, Moscow, and Tallin. Other colonists settled in Astrakhan, Sarepta, Ukraine, and Estonia.

Several routes were taken to the lower Volga. Not all of the colonists survived the trek to the lower Volga. Of the 26,676 colonists dispatched from Oranienbaum, 3,293 (12.5%) died in route.

Transport lists were compiled as colonists arrived in Saratov by Russian army officers who escorted the transports. In addition to the names of all members of the family and the ages of the children, births and deaths were listed. These lists were not completely preserved. The years of 1766 and 1767 were covered but the exact dates of each transport are not indicated. There are a total of 7,501 individuals mentioned on the nine transport lists.

From Catherine to Khrushchev: The Story of Russia's Germans by Adam Giesinger

German Migration to the Russian Volga (1764-1767): Origins and Destinations by Brent Alan Mai and Dona Reeves-Marquardt

St. Petersburg: Architecture of the Tsars by Dmitri Shvidkovsky

The Volga Germans: Pioneers of the Northwest by Richard D. Scheuerman and Clifford E. Trafzer